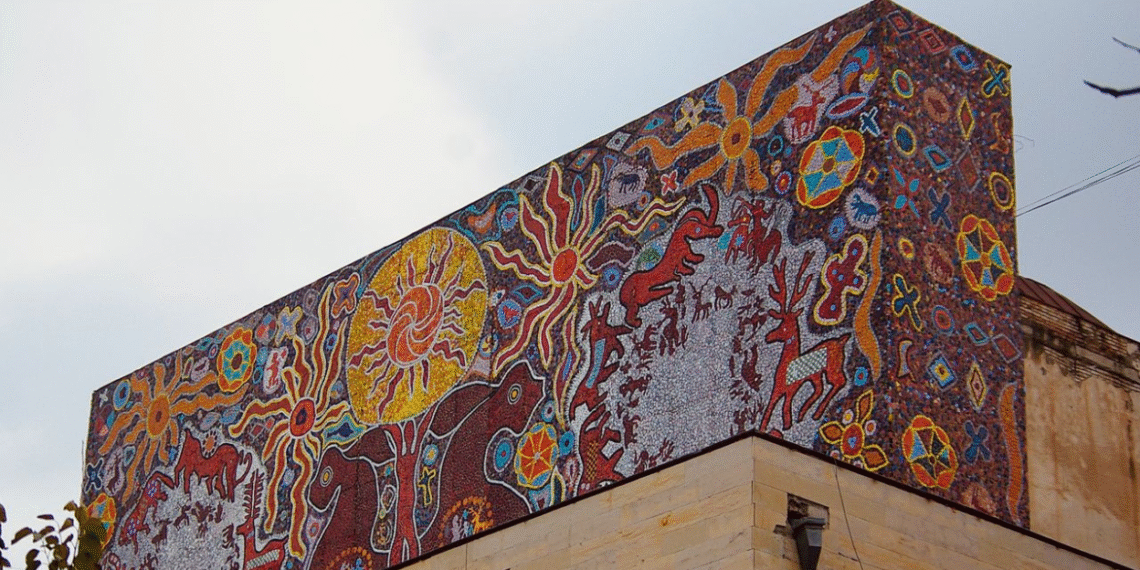

If you’ve ever taken the Tbilisi metro or traveled through Georgia’s regions, you’ve likely noticed the giant, colorful mosaics scattered across public squares, building facades, and even bus stops. These monumental artworks are more than decorative relics — they are vivid reminders of a not-so-distant past.

A Brief History of Mosaic Art

Mosaic as an art form originated in ancient Greece, where it was considered a marker of wealth, status, and cultural sophistication. The earliest mosaics were crafted from pebbles, with artists carefully selecting naturally colored stones to create geometric patterns. In Greece, mosaics were primarily used to embellish floors, turning ordinary spaces into immersive works of art. The Romans inherited this tradition from the Greeks but elevated it to new heights. They expanded its use beyond floors to walls, ceilings, and fountains, filling villas and palaces with scenes of hunting, daily life, and mythological narratives. In Roman society, mosaic decoration became a key indicator of luxury and social prestige.

Mosaic in the Soviet Union: “Art for the People”

In the Soviet era, mosaics took on a radically different function — they became powerful tools of ideology. Party leaders proclaimed mosaic as “art for the people,” embedding it into the very fabric of public life. Monumental compositions were commissioned for the facades of factories, checkpoints, schools, and cultural centers. These striking, large-scale works were designed to immerse citizens in the ideals of socialist realism, labor, and unity. Their grand scale and vivid glow weren’t just for decoration — they were carefully staged to captivate the passerby, leaving a lasting impression and gently steering citizens toward the collective rhythm of state life.

The “Monumentality Effect” — What Lies Beyond the Mosaic

One question inevitably arises: why were Soviet mosaics so massive? The answer is simple — they were designed to be grand enough to make the viewer feel small, almost insignificant, especially in the face of the sweeping collective idea the state was so eager to communicate through ornamented compositions.

In psychology, this phenomenon is sometimes called the “monumentality effect.” When an object’s scale exceeds that of the human body, it creates an almost visceral illusion of power. Such visual dominance can change behavior — encouraging obedience, rule-following, and, most importantly, a sense of belonging to something larger than oneself. This was exactly what the Soviet authorities wanted: mosaics that would soften individualism, dissolve the personal “I,” and reframe meaning through the lens of collective purpose.

The Story of Mosaic Art in Georgia

In Georgia, mosaic art reached its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, a period when censorship slightly loosened and artists were granted more creative freedom. Georgian mosaicists created a distinct “wall narrative,” unique in both style and quality. Among the most notable are Zurab Tsereteli, Gia Ryazanov, Nikoloz Tsereteli, and Nikoloz Ignatov, whose works blend Russian avant-garde, Constructivist influences, and native Georgian painting traditions.

Unlike the colder, rigid aesthetic of much Soviet art, Georgian mosaics radiate warmth and color. They often feature naturalistic details and weave together scenes of rural and industrial labor, Soviet athletic triumphs, and motifs from Georgian history, folklore, and landscape. Grapevines, clusters of grapes, the sun, and the moon — our enduring national symbols — frequently appear, while some works even include historical figures such as King Vakhtang Gorgasali or King David the Builder, reframed as forerunners of the communist ideal. By harnessing the monumentality effect, these artists created imposing works that, despite their scale, communicated a subtle but powerful sense of cultural identity, a quiet assertion of national spirit in the face of ideological pressure.

Today, they remain not just Soviet artifacts, but lasting monuments to the artists’ ability to merge propaganda with poetry. And if you find yourself in Georgia, you can still witness these mosaics in their original settings: from the industrial and construction-themed panels in Tbilisi’s Didube metro station to the dynamic sports-themed mosaic at Kutaisi’s Palace of Sports. Zurab Tsereteli’s early work “Evening by the Sea” in Batumi perfectly captures the blend of monumentality and coastal romance, a reminder that even under Soviet rule, art could speak in more than one register.

The Place and Role of Soviet Mosaics in Contemporary Georgia

Some mosaics have withstood the test of time and remain beautifully preserved. Others, however, are in urgent need of restoration to maintain their aesthetic and historical value. Sadly, many are in danger of disappearing altogether — damaged beyond repair or left to decay in the open air.

Public attitudes toward these works remain divided. For some, they are nothing more than symbols of Soviet propaganda; for others, they are historical artifacts, telling a visual story about art, politics, and culture under an authoritarian regime.

This is a crucial conversation about memory and heritage. In recent years, new movements have emerged with a mission to catalog and document these mosaics before they are lost. Urbanists and cultural activists are creating online maps marking each mosaic’s location and condition. For Generation Z, these works are often viewed less as ideological statements and more as photogenic backdrops — something to capture for Instagram. Their focus has shifted toward aesthetics, even if the historical context recedes into the background.

Yet this social-media-driven fascination is not without value: by sharing images of mosaics online, a new wave of awareness and appreciation is taking root, which may ultimately aid preservation efforts. These works are not just relics of a bygone regime — they are integral pieces of Georgia’s cultural heritage. They tell a dual story: of how the state sought to shape its citizens, and of how artists found ways to bend, reinterpret, and quietly resist, keeping national identity alive within the constraints of ideology.

Text: Tatuli Ghvinianidze